Diana and Francesco As Diana’s career as a printmaker flourished in Rome, her husband, Francesco da Volterra, experienced comparable success as an architect. To Renaissance eyes, Diana’s association with Francesco was as important as her artistic skill. The couple became a model husband-and-wife team – a good way to reassure patrons of Diana’s womanly virtue, despite her dubious participation in the commercial realm. In reality, Diana’s collaborations with her husband yielded a number of fascinating works, among them an astrological calendar and a large-scale architectural illustration

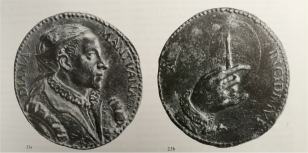

Diana Scultori (ca. 1535-1612) and Francesco da Volterra (1535-1594)

Volute of a Composite Capital, 1576

Engraving 30.3 x 44 cm

Biblioteca Alessandrina, Rome (Image from Lincoln 1997)

Diana based this work on one of her husband’s architectural drawings after a column capital in Saint Peter’s in the Vatican. Though the print’s style is ornamental and illustrative, its unusually large size and proud inscription raise is to a higher level of art.

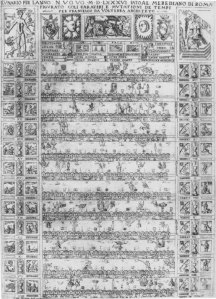

Diana Scultori (ca. 1535-1612) and Francesco da Volterra (1535-1594)

Lunario for the Years 1584-1586

Engraving 44 x 32 cm

Biblioteca Angelica, Rome (Image from Pagani 1991)

Another print after a design by Francesco, this large and complex work would have been used as an astrological calendar. Surrounding the central chart are images of Olympian gods, signs of the zodiac, and labors of the months, along with a nude figure demonstrating the effects of celestial phenomena on the human body. The papacy took some steps toward regulating the production of calendars and astrological treatises during the latter half of the sixteenth century, and a 1586 Bull against astrologers may have stifled the production of lunari in the subsequent years.

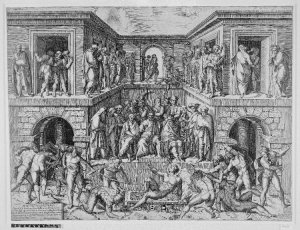

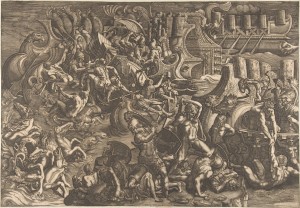

Diana Scultori (ca. 1535-1612) after Baccio Bandinelli (1493-1560)

The Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence, 1582

Engraving

44.3 x 58 cm

British Museum, London

As Francesco’s wife, Diana became an honorary citizen of Volterra. Always the opportunist when it came to marketing her work, she signed a number of her works “Citizen of Volterra” in addition to the usual “Mantuana” (“of Mantua”), affirming her ties to numerous cities and courts throughout Italy. This engraving, depicting Saint Lawrence being grilled alive over burning coals, is dedicated to a member of the Medici family, then rulers of Tuscany and Volterra.

Diana’s Later Works

Although Diana made her reputation through large and ambitious works dedicated to courtly patrons, the majority of her prints are on a more modest scale. As was the case for most engravers of the period, private devotional works and images of classical statuary, to be distributed by a commercial publisher, provided constant employment and a steady income.

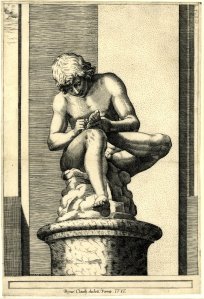

Diana Scultori (ca. 1535-1612)

Spinario, 1581

Engraving

30.5 x 21 cm

British Museum, London

The Spinario sculpture, depicting a boy extracting a thorn from his foot, was one of the most widely admired antiquities in Rome. Drawings and prints after the work were in high demand. This engraving was published in 1581 by Claudio Duchetti, who had taken over the prestigious Lafreri workshop after the master’s death, and whom Diana may have known through her brother Adamo, one of the heirs to the Lafreri estate.

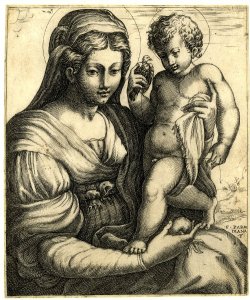

Diana Scultori (ca. 1535-1612) after Parmigianino (1503-1540)

Virgin and Child with a Bird, 1580s

Engraving

16.8 x 13.7 cm

British Museum, London

This humble work shows Diana’s mastery of her art. The textures of the hair, skin, and drapery are all beautifully rendered, the hands of both figures elegantly stylized.

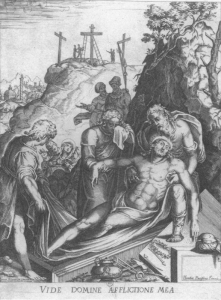

Diana Scultori (ca. 1535-1612)

Deposition, 1588

Engraving

39.1 x 28.1 cm

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris (Image from Lincoln 1997)

Diana’s latest dated prints are from 1588. It was once assumed that her grief at the death of her husband, as expressed in the inscription on this image of Christ’s Deposition (“See, Lord, my affliction”), made her quit making prints. In fact, Francesco did not die until 1594, and the alternate hypothesis that the “afflictione” in the inscription refers to Diana’s arthritis, is equally fanciful. Diana was married again, in 1596, to another architect, Giulio Pelosi. Though no dated works survive from the period after 1588, it is likely that she continued to print from her old plates and possibly made money by selling off the rights to her images. She died in 1612.

Further Reading and Links:

Lincoln, Evelyn. The Invention of the Italian Renaissance Printmaker. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2000, 111-145.

Lincoln, Evelyn. “Making a Good Impression: Diana Mantuana’s Printmaking Career.” Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 50, No. 4 (1997), 1101-1147.

Pagani, Valeria. “A Lunario for the Years 1584-1586 by Francesco da Volterra and Diana Mantovana.” Print Quarterly, 8, No. 2 (1991), 140-5.

Witcombe, Christopher L. C. E. Print Publishing in Sixteenth-Century Rome: Growth and Expansion, Rivalry and Murder. London and Turnhout: Harvey Miller, 2008.

http://clara.nmwa.org/index.php?g=entity_detail&entity_id=7268